(This is a piece I wrote in 1992, with hopes of getting it reprinted in, say, The New Yorker or The Chronicle. For some reason, I put it away in a drawer and found it the other day. To make complete, I have added some things that have happened since then. But generally, it is an innocent look at a time long ago.)

Producer

My company writes radio commercials and, not long ago, we came up with one for the major league baseball team here. It was a song that four or five singers would perform a cappella, in the style of a black street corner group. Naturally, we called Allen Toussaint.

If you’re a red-blooded American with a radio in your car, you’ve heard music Mr. Toussaint has written – songs like “Mother-in-Law,†“Working in the Coal Mine,†“Fortune Teller,†and “Southern Nights.†He is perhaps better known, however, as a music producer. Over the years, from all over the world, such people as Paul McCartney, Ramsey Lewis, Etta James, Albert King, and Joe Cocker have travelled to Mr. Toussaint’s little studio in New Orleans to be encouraged, cajoled, directed, exhorted, persuaded, and in a sense tricked into doing their finest work.

On the phone I asked Mr. Toussaint whether he liked baseball, since that’s what our song was all about. “No,†he said. “But I’m glad it’s there.â€

His studio is about five miles east of New Orleans, in the Gentilly neighborhood, a place that probably looked better twenty years ago. You pass barred storefronts with Dixie Beer and Po’ Boy signs. You pass untold kids on banana seat bikes. You pass those Greek Revivalist houses as narrow and long as train cars. Sea-Saint Studios (Half Toussaint and half Marshall Seahorn, his business partner) is a cinder-block building next door to a market.

(Note: Sea-Saint disappeared under three and a half feet of water in Hurricane Katrina. It was never rebuilt.)

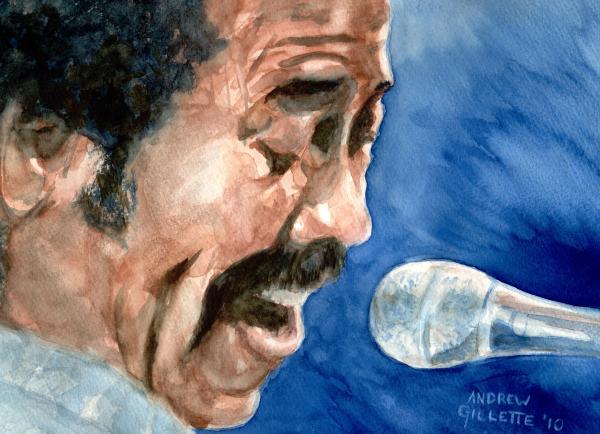

After a short wait – there is a lot of waiting in New Orleans, though nobody there seems to notice and, after a while, neither do you – Mr. Toussaint came out to meet me. He is in his early fifties and is wearing a blue silk suit, a tie that featured a hand-painted Japanese character, and a large gold medallion which hung from a chain around his neck. He looks a little like a miniature version of Willie Stargell, the baseball player. (Baseball seems to be a recurrent theme here.) All that aside, however, the thing you notice about him – it’s in the Caribbean overtones of his voice, in the way he moves and the way he cocks his head to listen intently – is a sense of true gentleness. “How are you doing?†I ask him. “Well,†he says, as if he’s going to go on and say something else. It is the answer he usually gives, and he really seems to mean it.

The thing about producing music is that it’s mind control. It’s manipulating someone’s talent and environment in such a way as to elicit a great performance. Producers typically have to dispel nervousness, create nervousness, encourage anger, honor outlandish requests, battle outlandish requests – all according to the situation at hand. Volatile, dictatorial producers are not uncommon. Neither are obsequious, ineffective ones. Of course, that’s what makes Mr. Toussaint’s gentleness so remarkable. It works. He’s like the non-violent opposition leader in a country of egotists, eccentrics, and obsessives.

Four hours pass. The singers are here and he’s rehearsing with them. One of the tenors, a tall guy named Roland with a shaved head, is having trouble with a harmony. “Sing it again, please,†Toussaint tells him. Roland does. “Again, please.†Roland does. “Do you hear it?†“No.†“Sing it again, please.†Finally, after perhaps ten times around Toussaint sings it himself: “Ba-ba-ba-ba-BA.†It sounds pretty good – very good, in fact. Roland smiles: “That was great. You should do it yourself.†“No way, young man,†says Toussaint. “That’s your job.†Roland smiles bigger.

Mr. Toussaint’s ear for pitch is legendary. During recording sessions, he plays performances over and over, sometimes swaying and clapping his hands as he listens, sometimes sitting with eyes closed, chin in hands. There is no sign that he feels something is, as he says, “a semitone off.†But after a while, you just know that’s what he’s thinking. The musicians know it. The sound engineer knows it. Over and over it plays, while everyone strains to hear what Toussaint hears. There’s a lot of momentary eye contact like Okay the lights are back on now, so who’s got the gun? Then he’ll say: “Listen to this part right here, gentlemen.†And sure enough, there it is, big as life. Everyone files back to their places to record it again. “This is it,†Toussaint will tell them. “I can feel it. It’s coming. This is the one.â€

The rehearsal is over and a funny thing happens. Mr. Toussaint says he has a couple of errands to run. He tells the singers to record the two basic soundtracks of the music while he’s away. “We’ll put in the harmonies later,†he tells them. They all nod. He’s gone. The singers get right to work. One of them, a guy the others call “Bunchie,†steps out and leads the group, still singing himself. A half-hour later, the tracks are recorded. “You like them?†they ask us. “You happy?†We are.

A few hours later, in what is now the wee hours of the morning, Allen returns. He settles into a chair as the engineer rewinds the tape for a playback. The room falls silent. Eyes dart from face to face. Legs wiggle. Knuckles crack. It’s like: Who’s got the gun?

“An interesting piece.†He says, when it’s over. “Very interesting. May I hear it again, please?†It’s not really a question. Who’s got the gun?

“Once more, please.†Who’s got the gun?

Then finally: “Gentlemen, listen to the first two bars in the second part and tell me what you hear.†The singers smile knowingly. We’re here for the night.

If there is a pattern to Mr. Toussaint’s method, perhaps it is: “I am in charge here. I am responsible. Therefore, it is my opinion and taste that will prevail. Get to know me. Try to see and hear things as I do. I will give you time.†It is a gentle yet commanding kind of control, the effect of which is nowhere more evident that when Toussaint gives praise. After hours of exhausting, repetitious work, he has a way of eliciting big proud smiles from everyone with a perfectly-timed “My yes!†or “Get down!†or “All right!†The latter, delivered with a soft conviction, is one of the sweetest compliments imaginable.

During a break, the singer named Manuel tells me he’s never sung for Toussaint before. He considers tonight a singular honor. “I’m a hospital orderly in the daytime,†he says. “When the call came in, the nurse took it and she says, ‘It’s Allen Toussaint.’ I said, ‘Yeah. Right.’†Hours later, well after 2:00 a.m., when Toussaint finally tells them “Gentlemen, I think we have something to work with here,†it is Manuel who looks most pleased.

Toussaint’s car edges slowly through the early morning crowd in the streets of the French Quarter (“The Quarters,†he calls it, like a lot of locals). He’s giving me a ride back to my hotel in his vintage Bentley. I’m talking to break the silence. After years of producing albums, I suggest to him, a one-minute commercial must seem pretty easy. “You’d think so,†he says. “But not at all, not at all. Although it’s shorter than an album cut, it must still be written, arranged, sung, and played. And it’s still music.†He looks at me, quite seriously. “It must be perfect.â€

At nearly every corner, there are faces at his car window, knocks on the hood, greetings. Toussaint smiles and waves, says little. The lights of the city crawl slowly up his face as the car inches forward.

“Hey, Allen,†say the voices. “You got me a gig or what?â€

“How ya doin’, boss?â€

“You been to hear Ernie? The cat is blowin’, man! He is blowin’!â€

Toussaint, looking less tired than anyone we see, just smiles.

Leave a Reply